Wednesday, November 12, 2025

BY TRACY HOFFMAN

My Washington Irving class completed our reading of A Tour on the Prairies today. If some of you were working through the text along with us, congratulations! We made it to Chapter 35.

I would like to thank Cheryl Weaver for crafting two wonderful blogs during the Halloween season while teaching “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” She gave me a few weeks to catch up, and it was better to hear about “Sleepy Hollow” during October than Irving’s buffalo hunt. Thank you, Cheryl. You’re awesome!

In the next few weeks, I’ll try to touch on themes my class discussed on our adventure through Oklahoma Territory with Washington Irving, but for today, I want to focus on one overall idea we used in the classroom–chautauqua.

The class concluded our study with a Zoom chat featuring Dr. John Dennis Anderson, who performs as Washington Irving. Another special thanks goes out to John for spending time with us today. Thank you! Thank you! John told the class how fortunate they were to have Dr. Hoffman as their instructor, and I reminded them of how lucky they were to have John Anderson join them for a conversation.

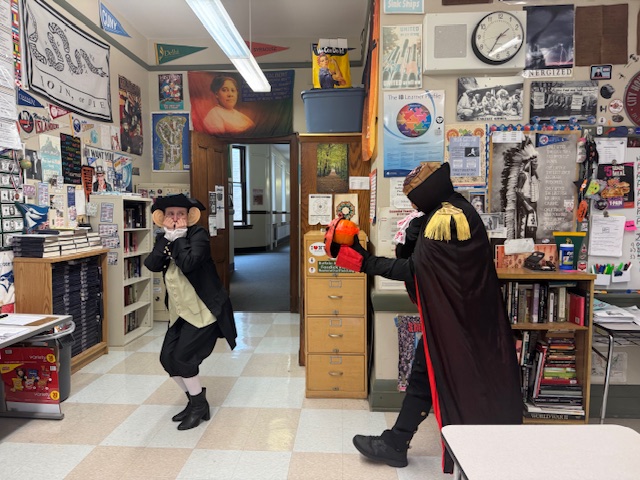

Awhile back, after having my class watch John’s performance on YouTube, I decided to experiment with chautauqua in the classroom. As I told John later, he makes it look easy, but it’s not that easy. Despite the challenges, the experience was still a fun classroom experiment. I would highly recommend teachers of literature apply such a technique to their teaching repertoire.

At the beginning of our journey through Irving’s book, I assigned each student one of the following characters or people groups. Their goal was to focus on these folks during the readings and be prepared to report on the assigned characters for upcoming reading quizzes:

- Washington Irving, the narrator

- Swiss Count (Albert-Alexandre de Pourtalés)

- Mr. L (Charles Latrobe)

- Commissioner/Rangers

- Tribes

- Settlers

- Antoine (not Tonish)

- Tonish (Antoine)

- Pierre Beatte

I’ve done this sort of thing before, most often when I teach Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club. Following one of the four mothers or one of the four daughters works great for keeping up with the very detailed reading. Anyhow, beyond a close reading of characters, I added a chautauqua component.

Instead of giving students a quiz at the beginning of class to check their reading, I gave the quiz at the end of class, after we had chatted about the reading, from each character’s vantage point. It was uncomfortable at first, but I forced everybody to do their best to get into character, to have a conversation as if your characters were sharing “round the campfire,” like Irving and his companions spend their evenings on the prairies talking about the day’s events.

For a performance, John Anderson typically appears in character for the greater portion of his time and then steps out of character for the final part. However, my students and I were not able to stay in character for long. We found ourselves wanting to step aside and add commentary and ask questions, so we simply modified the process to flow in and out of character as needed.

For three classes, we followed a chautauqua-style conversation, which forced students to move their chairs, get out of the regular rows, and face me and each other. This shook a few of my “back row Baptist” students into a more significant role in the conversation. I really enjoyed hearing these students open up, and I hope they enjoyed playing a greater role in our chats.

For three classes in a row, I added to our makeshift “campfire.” At first, it was only an old Baylor popcorn can with construction-paper cut into flame-shaped shards of red, yellow, and brown. I’ve heard tissue paper works better, but I didn’t have any of that on hand.

On Wednesday of last week, I exited my car, after arriving on campus, and immediately spotted a nice log—a branch which had obviously fallen during recent storms. I carefully lugged it to my office, where it sat in the hallway until class time. One of my colleagues passed by my office that day and said, “I like your log,” and kept walking.

One of my friends over the weekend said we needed smores, but I said no, since Irving had zero smores on the prairies. He did, however, have brown sugar with his black coffee. I scrounged up a canister of Folgers from the faculty lounge, but my personal coffee maker needed cleaning before sharing it with students. Next time I teach the book, I’ll be sure to reenact all the coffee drinking, which I appreciate.

My students told me we needed rocks to properly set up a campfire, so I “borrowed” a bag full of rocks from a lovely flower bed. (Hopefully, my HOA didn’t notice my digging in the flower beds on the security camera.) My students weren’t fans of the rocks I gathered, since they weren’t big enough to enclose a real campfire. Again, I have goals for the next time I teach the book.

It’s getting late, and I still need to return the rocks to their proper home, so I’ll stop for now. I’ll catch you next week for more debriefing about Irving’s Tour on the Prairies. Until then, you can check out one of John’s performances: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXCoEwa2dqk