November 5, 2025

BY CHERYL WEAVER

“Irving is really haunting the text!”

—11th-grade student after class

I was initially uncertain about how to teach this text. Irving’s work had never appeared in any anthologies my district provided, and I hadn’t encountered Irving—at least in my memory (a Rip Van Winkle moment?)—until graduate school. I developed three main instructional objectives:

- Thematic: The story serves as part of the narrative of a new nation, emphasizing identity as beyond the individual and situated within societal constructs.

- Comprehension: Focus on Irving’s detailed descriptions of characters and settings, helping students understand why he invested so heavily in these descriptions.

- Vocabulary: After reviewing the story, I identified a few words that might require additional support for my students.

Here’s an overview of the short plan I developed, incorporating various activities:

Day 1: Students were tired from taking the PSAT in the morning, so to introduce the story, I showed the 1949 Disney adaptation. We used a short worksheet to explore questions about the post-WW2 context and what this adaptation reveals about the United States at that time.

Days 2-4: I gave a brief PowerPoint presentation on Irving and began reading the story with the students. Using an “I do, we do, you do” approach, I read and annotated the text on the first day, having students note brief subtopics for each paragraph. This helped them practice organizing their writing. On the second day, we annotated together, and on the third day, students read and annotated a section individually. We concluded with a 20-question multiple-choice assessment to gauge their understanding and identify areas needing review.

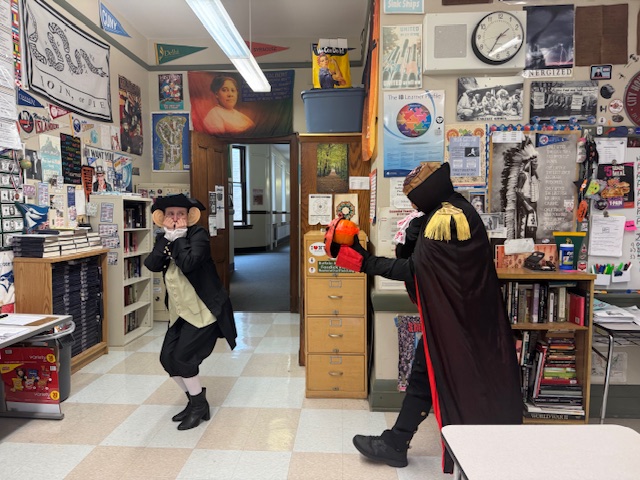

On the last day, Halloween, I read the story’s conclusion dressed as Ichabod Crane. To strengthen cross-curricular connections, this unit aligned with the students’ AP U.S. History studies; their history teacher dressed as the Headless Horseman!

To further engage students and assess their understanding of the text’s connections, we started two class days with a game I designed. Topics included natural imagery, real and fictional characters, settings, and vocabulary, specifically focusing on last names and the term “cognomen” from “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

Overall, students enjoyed the unit and made insightful connections between Irving’s role in crafting history and identity for the newly formed nation. One student remarked, “Irving is really haunting the text!”

Now, I’m beginning to introduce “Rip Van Winkle,” aiming for a culminating project where students can choose between a creative writing option, a traditional analysis essay, or a visual design incorporating elements of Irving’s story and themes.

I eagerly anticipate sharing my students’ creations with you!